Jun 18, 2015

CPI Europe Column edited by Anna Tzanaki (Competition Policy International) & Juan Delgado (Global Economics Group) presents:

Should Uber be Allowed to Compete in Europe? And if so How? by Damien Geradin1 (EDGE Legal)

Intro by Juan Delgado (Competition Policy International)

The disruptive market entry of Uber has generated lively debate, several taxi drivers demonstrations and a number of court decisions all over the world. The question of whether such entry should be accommodated or banned by regulators has been the object of thoughtful analysis by policy-makers, judges and scholars. Damien Geradin goes a step forward and, recognizing that sooner or later innovative services will find their way to the market, explores different alternatives of making such transition smoothly and compatible with EU and domestic regulations

Abstract

Uber’s arrival in Europe has generated massive demonstrations by taxi drivers and a number of court judgments banning or restricting Uber’s services on the ground that the company engaged in “unfair competition”. Uber and other online-enabled car transportation services to connect passengers with drivers offer an attractive alternative to regular taxi services. The difficulty is that these services are protected by regulatory measures that create significant barriers to entry. Uber’s business model presents many efficiencies and there is little doubt that it will prevail over time. Regulatory authorities thus face two options. One option is to resist the market entry of Uber and other similar companies. This approach would deprive users of attractive services and trigger many years of litigation. The other option is to embrace technological change and allow Uber to compete on a level playing field with taxi companies. The regulatory changes that will be needed raise complex questions, but these questions are unavoidable and it is important to tackle them early. Taxi companies can also embrace technologies and rely on the competing online-enabled car transportation services that are already available to them.

Keywords: Taxi services, Uber, regulation, competition, regulation, disruptive business models, online platforms.

JEL codes: K21, K23, L43, L44, L50, L62, 033

Introduction

While many industries are characterized by constant innovation, the development of the peer-to-peer economy has injected dynamism in industries, which for a long time operated under static business models. That is, for instance, the case of the taxi industry. For almost a century, taxi companies in all parts of the world relied on a similar business model. Passengers can hire taxis by queuing at a cab stand, by hailing them in the street or by making a telephone reservation. Historically, technology played little role in the industry, which is not surprising since taxi services are subject to barriers to entry created by regulatory intervention. Taxi regulations, for instance, limit the number of vehicles authorized to provide taxi services in a given locality. This would not matter so much if the industry was characterized by high levels of performance. However, taxi fares remain often expensive while the quality of the service can be mixed. At certain periods of the day, taxis tend to be scarce. Users may thus experience long waiting times and, in some cases, taxis do not show up at all. This led some countries to engage deregulatory initiatives to improve the performance of the taxi sector, but the often reverted to regulation given the mixed results of these initiatives.2 Until recently, it seemed that this sector was not called to evolve and that users would have to put up with the service as it is.

This situation changed with the arrival of Uber and other providers of what I will refer to as online-enabled car transportation services to connect passengers with drivers.3 While Uber likes to call itself as a ride- or car-sharing service, the ride or the car are not truly shared. What characterizes Uber compared to regular taxi services is that it is a marketplace where independent drivers are connected to passengers through an online platform. Uber’s mobile app is user-friendly and its rates are generally attractive compared to the rates charged by regular taxis.4 That made the service popular in many cities. While Uber has aficionados among users and investors,5 it has however a large number of enemies in the taxi industry. The arrival of Uber in Europe has triggered massive protest from taxi drivers and companies on the ground that Uber does not comply with taxi regulations and therefore engages in “unfair competition”.6 This led taxi companies to seize the courts and Uber activities have been banned or subject to serious restrictions in Member States, such as Belgium,7 Germany,8 Italy9 and Spain.10 Although some public authorities are considering changes in the applicable regulatory framework in order to accommodate Uber and similar companies,11 the situation remains chaotic.

Against this background, this short essay argues that the restrictions that have been placed on Uber’s activities are undesirable as they deprive users of an attractive and innovative alternative to regular taxi services. While some of these restrictions can possibly be challenged under EU law, this does not mean that Uber should be allowed to operate in a legal void. Innovation does not alter the need for measures designed to ensure public safety, as well as to protect users from various categories of risks. This means that the regulatory framework should be adapted to allow Uber to operate legally, as well as to compete on a level playing field with taxi services. The legalization of Uber and similar services raises, however, a number of complex issues that will only be briefly touched upon in this essay. A complex question is, for instance, whether online-enabled car transportation services and taxi services should be subject to the same regulatory regime or to separate regimes adapted to their characteristics. Another question is whether taxi companies and/or drivers should be compensated for the loss of the investment that they may have made in, for instance, acquiring a license, the value of which will considerably decrease following Uber’s market entry. These questions will be briefly examined in this essay and looked at in greater detail in a subsequent paper.

This paper is divided in VI sections. Section II provides a brief history of the regulation of taxi services, which in some cities is almost one century old. Section III describes Uber’s business model and how it contrasts with the services provided by traditional taxi companies. Section IV discusses the EU law provisions that could be used by Uber and other similar companies to challenge the regulatory restrictions that prevent them from offering their services in many parts of the EU. Section V argues that the way forward is for the relevant public authorities to revisit the regulatory framework applied to taxi services in order to allow Uber to compete legally against taxi companies. Section VI concludes.

A brief history of taxi regulation

Although taxi services are fairly basic in nature (transporting passengers from point A to point B) and do not require much capital or skill (a car and a driver), they have been for a long time subject to fairly intrusive regulation with variations across countries and localities.12 Among the reasons evoked for regulating taxi services figure, for instance, the fact that in the absence of control on entry there would be too many taxis in the streets and this would create congestion.13 There has also been a fear, particularly during the great depression, that if taxis were in excessive numbers, they would engage in ruinous competition, which would in turn lead to low quality of service.14 Regulation has also be seen as necessary to correct information asymmetries as, in the absence of rate control, consumers would have no guarantee that the fares they pay are fair and reasonable.15 Similarly, besides having a superficial look at the aspect of the car, users have no means to know whether they will be driven in a safe vehicle. Hence, regulatory requirements are needed to ensure the safety of passengers.

As a result, with some degree of variation, regulation of taxi services typically involves: (i) control of entry (with local authorities, for instance, setting the maximum number of vehicles that can be used to provide taxi services); (ii) licensing and performance requirements (for the drivers and the taxi companies) designed, for instance, to ensure safety standards for both drivers (who need to receive proper training) and vehicles (which must be inspected on a regular basis); (iii) financial responsibility standards (such as compulsory insurance); and (iv) the setting of maximum rates based on various methodologies.16

The regulation of taxi services created, however, a series of problems, such as for instance the insufficient availability of cars during peak hours or in certain areas (seen as less profitable by drivers). In many instances, efforts to prevent the oversupply of taxi services effectively led to an undersupply of such services leading to user discontent.17 With the prices and quality standards set by public authorities, taxi regulations also did not incentivize taxi companies to innovate or provide superior quality of service. This led some countries or local authorities to deregulate taxi services.18 While in most cases, the number of taxis increased, this did not necessarily translate into lower waiting time and cheaper services. In fact, some studies report that service performance often decreased following deregulation,19 which led authorities to re-regulate the sector.20

A critically important aspect is that these deregulatory efforts did not lead to major innovation as new entrants essentially used the same business model as incumbents. Of course, these efforts occurred for the most part before the development of the peer-to-peer platforms, which, as observed in several industries (air travel, hospitality, etc.), are true game changers in that they are remarkably effective at matching the demand with the supply of services without the need for costly intermediaries. Thus, the fact that deregulation did not bring innovation in the past does not mean that it will not happen in the future.

Uber’s disruptive business model

Uber is a marketplace connecting drivers offering rides and passengers seeking them through its mobile application.21 A prospective passenger who has downloaded the software on his smartphone and set up a user account can, when clicking on the application, see Uber drivers near his location and on that basis submit a trip request which is then routed to the drivers. The passenger is given an estimation on how long his car will take to show up at his location. Uber charges are based on a combination of time and distance parameters and all payments are handled automatically by the Uber service, which will charge the passenger’s business card on file. Once destination is reached, a receipt is sent automatically to the passenger’s email address. On average 80% of the fares will go to the driver, the rest being kept by Uber.22

The strength of the Uber model is that it considerably reduces search costs for users.23 Rather that calling a dispatcher and waiting without knowing for sure whether and when the taxi will show up, users can hail a car through Uber’s online platform and watch it progress toward their location. During periods when available cars are scarce (e.g., Friday and Saturday nights), Uber can incentivize drivers to take the road by increasing their fees (a process referred to as “dynamic” or “surge” pricing).24 Dynamic or surge pricing changes are “driven algorithmically when wait times are increasing dramatically, and ‘unfulfilled requests” start to rise.”25 Prices increase will at same time increase supply as drivers will be incentivized to take the road to earn higher fees, but also reduce demand as price-sensitive users are incentivized to consider alternatives, such as take their car or public means of transport.

In sum, Uber’s business model offers several advantages to users. First, the software is extremely easy to use and it gives users a clear indication of where the car they have just hired is located, as well as the ability monitor its progress on the screen of its mobile devices. This reduces the anxiety associated with desperately waiting for a taxi. Second, surveys suggest that compared to regular taxi services, Uber prices tend to be attractive.26 Third, there is no need for users to carry cash or cards as all transactions are performed electronically. Finally, users can rate their driver and thus incentivize the driver to provide good service in order to boost his or her reputational score.

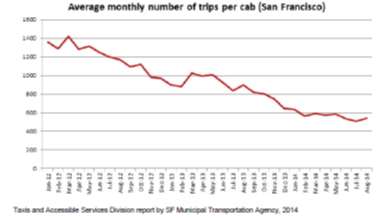

Because of its attractive features, Uber’s entry on a given market is usually bad news for taxi companies and their drivers. For instance, the chart below indicates that during the period between January 2012 and August 2014, cab use in San Francisco declined 65%.27

This has led taxi drivers to vigorously protest against Uber’s effort to penetrate their market, as well as taxi companies to challenge the legality of Uber’s activities before the courts. In recent months, several national courts declared that Uber services are illegal on various grounds (such as, for instance, the fact that Uber drivers operate without a license and that Uber engages in “unfair competition”).28 As a result, Uber is no longer able to provide services in some EU Member States and operates in a “grey zone” in many others. This is far from ideal for Uber and the passengers who would like to use its services.

The question for Uber is of course to find out what it can do to restore its ability to provide its service unimpeded by regulatory restrictions. As will be seen in the next section, EU law may provide some solutions.

Could public restrictions preventing Uber to compete be challenged under EU law?

Although Uber has announced that it has filed a complaint to the Commission against the German and Spanish bans of its services,29 it has not revealed the legal arguments on which it relies in its complaint. Prima facie, the EU treaties contained several provisions that can be invoked by companies whose activities are impeded by public restrictions of competition. Whether these provisions can be relied upon to challenge these restrictions, however, depends on the circumstances of each case since the regulatory frameworks applicable to taxi services can vary considerably.

A first possibility for Uber would be to invoke Articles 101 and 102 TFEU with Article 4(3) TEU,30 which provides for a duty of loyal cooperation between the EU and the Member States.31 In its case-law, the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) has found that a Member State could breach its obligations under these provisions by adopting or maintaining legislation that could deprive the competition rules of their effectiveness.32 The application of this case-law, however, requires the existence of an agreement contrary to Article 101(1) TFEU, which will be strengthened or encouraged by the legislation in the Member State.33 In some cases, the CJEU also found that Article 101 TFEU and Article 4(3) TEU were breached when the Member State had delegated the power to fix prices to operators.34 In practice, this means that a pure regulatory measure adopted by a public authority, i.e. a decree regulating taxi services, cannot be challenged under these provisions unless this decree transforms an anti-competitive agreement adopted by taxi operators into binding law or, alternatively, delegates to taxi operators the power to set taxi fares or impose other regulatory requirements.

Another possibility consists in invoking Articles 101 and 102 TFEU in conjunction with Article 106 TFEU. Article 106(1) TFEU provides that

“In the case of public undertakings and undertakings to which Member States grant special or exclusive rights, Member States shall neither enact nor maintain in force any measure contrary to the rules contained in the Treaties, in particular to those rules provided for in Article 18 and Articles 101 to 109.”

While there is an abundant case-law of the CJEU in which Article 102 TFEU is combined with Article 106(1) TFEU, the difficulty in this case is that the application of Article 106(1) requires that the State measure in question, e.g. a decree regulating taxi services, should benefit companies which have been granted exclusive or special rights. While it cannot be excluded that a taxi company could have been granted an exclusive right to provide the service in a given location, in the majority of the cases, the right to provide such services is granted to the limited number of companies or drivers that are allowed to acquire a license. The question is thus whether the licenses granted would amount to “special rights” as understood in EU law.35 While there is no clear definition of the notion of special rights (as the case law typically lumps together this notion with the notion exclusive rights by referring to “exclusive or special rights”), it can be inferred from EU legislation that “special rights” concerns rights that are granted by a Member State to two or more undertakings within a given geographical area.36 Moreover, given the combination with Article 102 TFEU, the State measure in question must maintain or strengthen a dominant position. Thus, even if the taxi companies can be considered as enjoying exclusive or special rights, they still need to exercise a “single” or “collective” dominant position, which is by no means a given.

A further possibility is to argue that the taxi legislation in question breaches the free movement provisions of the TFEU, such as Articles 49 (right to establishment) or 56 (freedom to provide services). As the CJEU observed “Articles [49 and 56 TFEU] preclude any national measure which, even though it is applicable without discrimination on grounds of nationality, is liable to prohibit, impede or render less attractive the exercise by Community nationals of the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services guaranteed by those provisions of the Treaty.”37 It should thus be possible to argue that taxi regulations making very hard for companies based in other Member States to provide their services could fall foul with Articles 49 and/or 56 TFEU. Restrictions to the free movement principles contained in the TFEU are, however, permitted when “those provisions are necessary to meet overriding requirements of general public importance […], whether they are proportionate for that purpose and whether the aims or overriding requirements could have been met by less restrictive means.”38 The question thus becomes whether the restrictions that are contained in taxi regulations in question are necessary to meet overriding requirements of general public importance and whether they proportionate to achieve the objectives they seek to protect. This is of course an intensely factual assessment.

While the above approaches may help Uber and other online-enabled car transportation services to remove specific obstacles to the provision of their services, they do not create a framework allowing regular taxi services and online-enabled car transportation services to compete on a level playing field. In my view, allowing competition between regular taxi services and online-enabled services requires an overhauling of the various lawyers of taxi legislation in place in the Member States.

The need for a regulatory solution

From a high-level standpoint, the most effective way to set up a pro-competition regulatory framework might be for the EU to adopt a Directive setting up the principles that should govern the regulation of taxi services and online-enabled car transportation services, while leaving the implementation of such principles to the Member States. Such an approach would, however, be resisted on subsidiarity grounds as such services are likely to be seen as a local matter.39 Moreover, the elaboration of a proposal by the Commission and its adoption by the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament would likely take several years to complete during which Uber and other similar services would continue to operate in a grey zone to the detriment of users. The better approach is thus for the national authorities in charge of regulating taxi services in the Member States to take the initiative and elaborate regulatory frameworks allowing taxi and online-enabled car transportation services to compete on a level playing field.

Conceptually, there are several alternative ways to create such a pro-competitive framework. First, regulatory authorities could create a single framework applying to both taxi services and online-enabled car transportation services. The advantage of such an approach is that it would ensure a high degree of convergence in the ways in which these services are regulated. Yet, this approach would face several difficulties. Because the services proposed by taxi companies and online-enabled car transportation services are currently so far apart, it may be difficult to find a regulatory regime suiting them both. While incumbent taxi companies may wish to ensure that Uber is forced to comply with the same regulatory requirements as applying to them, such an approach is a non-starter for Uber and other online-enabled car transportation services as it would eviscerate their business model. Ideally, taxi companies should realize that in the medium-term Uber’s business model is likely to prevail and that it is therefore a matter of time before they will have to revisit their modus operandi. In the short-term, such an approach is, however, likely to be resisted because it would lead to job losses, as well as an acceptance by taxi companies that the business model they have so much decried is the right way to go.

The commercial triumph of online-enabled car transportation services is, however, only a matter of time because of its inherent efficiencies. This is also what investors seem to think.40 Thus, unless local authorities decide to protect taxi companies through anti-competitive regulatory requirements, it will not take long before all market actors realize it is in their own benefit to start relying on online platforms. Some taxi companies already do so as alternatives to Uber’s platform exist.41 There might still be a role for traditional taxis waiting for passengers at cab stands, but traditional reservation models will likely go away. This type of evolution is by no means unique to the taxi industry as the power of the Internet and online reservation systems have already allowed consumers to largely do away with travel agents.42 There is no reason why you would want to pay a fee to an intermediary when you can book a flight, hotel accommodation and a car as effectively. The difference, however, between many industries affected by the online platforms and the taxi industry is that the latter is protected by regulation, hence making the transition slow and difficult.43

In the meantime, the better approach is probably to set up a new regulatory regime specifically designed for online-enabled car transportation services.44 The challenge for this regime will be to allow Uber and other similar companies to compete on the merits with regular taxi services. This means that this regime should be no less favorable than that the regime being applied to regular taxi services. After all, in all regulated industries, new entrants are subject to a lighter regular burden than incumbents. While there is perhaps no reason why Uber should benefit from a more favorable regime than taxi services, there is no reason either why it should penalized for offering an attractive alternative to these services and create competition in a rather amorphous sector. What equal treatment means is difficult to determine in the abstract as it largely depends of the local circumstances, but it should be one of the guiding principles of the regime that applies to online-enabled car transportation services.

Prima facie, some regulatory requirements should be equally imposed to taxi drivers and operators, and to Uber and its drivers. That is, for instance, the case of safety standards. There is no reason why Uber cars should escape the safety controls that apply to taxi vehicles. Similarly, Uber drivers should not be less qualified or trained than taxi drivers, and they should be subject to background checks. There may also be some areas where online-enabled car transportation services should be subject to regulatory requirements that do not necessarily apply to taxi services. One example relate to the usage of personal data. Uber is able to collect sensitive information about its passengers, such as their locations at various moments in time. They also collect financial information, such as credit card details, etc. It is, however, not clear that Uber and other online-enabled car transportation services should be subject to specific regulation regarding the storage and treatment of their passengers’ personal and financial data as “horizontal” legislation typically exists preventing holders of such data to misuse them.46

Now, if a specific regime is created for online-enabled car transportation services, it is subject to question whether taxi regulations should also be modified. Does it, for instance, make sense to continue to control taxi fares when they are subject to competition from Uber and other similar companies? This is a particularly difficult question, although one answer may be to maintain price regulation until such time online-enabled car transportation services have captured a certain size of the market (assuming that there are in the same market as taxi services, which is a complex question I do not address here) and are thus able to exercise sufficient pressure to keep taxi rates at bay.

Another complex question in this respect is whether incumbent taxi operators and/or drivers should be compensated for the investment they may have made in acquiring a license to operate taxi services. This question may be particularly acute in cities where such licenses (or medallions as they are called in some places) trade at very high prices.47 Giving the right answer to this question is not necessarily easy, although pioneering work has been done on this type of issue.48 On the one hand, offering compensation may facilitate regulatory change as it will make change easier to accept for the likely losers. On the other hand, granting compensation to taxi drivers or operators that have invested in acquiring a license may create a host of problems. First, compensation may not be deserved when the investment has been fully amortized. Second, compensation creates a problem of valuation.49 Calculating the amount to which a driver should be allowed will not be simple and alleged calculation errors will lead to litigation. Third, the prospect of obtaining compensation in case of change of regulatory regime may incentivize operators in a variety of fields to try to obtain exclusive or special rights from public authorities, hence reducing competition.50 Finally, as the taxi industry is not the only sector that is sheltered from competition by regulation, liberalizing the economy may become a very expensive proposition that may induce local authorities to not engage in desirable reforms. It thus seems on balance that there are more reasons not to grant compensation to taxi drivers or operators than to grant them compensation for the investment losses that may incur when Uber and other companies are allowed to operate legally.

Another possible approach to address the investment issue is to open the market to online-enabled car transportation services only gradually, hence giving taxi companies the time to adapt to the arrival of Uber and other companies providing similar services. That is the approach that has been taken by the EU when it decided to liberalize network industries, such as telecommunications, energy and posts. One of the reasons for this gradual approach is that it was a political compromise between pro-liberalization Member States and anti-liberalization ones. The need to broker such a compromise would of course not be needed if the decision to open the market to online-enabled car transportation services is taken at a local level. Moreover, the problem with gradual liberalization in this case is that it would unavoidably delay the benefits of competition by several years at the expense of consumers. In any event, opening the market in this case would be nowhere as near complicated in legal and institutional terms than opening the market in network industries, which for instance required the setting-up of access to the network regimes and the adoption of measures designed to protect universal service.

These are some of the difficult questions that will face local authorities seeking to develop a regulatory regime allowing online-enabled car transportation services to operate legally.

Conclusion

While Uber has been subject to a great deal of criticism, there is no doubt that it offers an attractive alternative to regular taxi services. There is therefore no reason why Uber and other online-enabled car transportation services to connect passengers with drivers should not be allowed to compete on a level playing field with taxi companies. Because taxi companies are protected by regulation, it is for public authorities to take the initiative. These authorities have two options. One option is to resist Uber’s market entry and face many years of litigation, which will eventually result in Uber being able to operate legally. The other, preferable, option is to embrace technological change and adopt a regulatory framework allowing Uber and other similar companies to compete. This does not mean that Uber should be allowed to operate free of regulation. For instance, passenger safety should remain a priority. As to the taxi companies, they do not need to remain passive bystanders waiting for their market share to be lost to Uber and other similar companies. They can also embrace change by, for instance, relying on other existing online platforms.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1Founding partner, EDGE Legal, a boutique competition and litigation law firm based in Brussels. Professor of Competition Law & Economics, Tilburg University; Professor of Law at George Mason University; visiting Professor, University College London. Email: dgeradin@edgelegal.eu

2See, e.g., Ambrosius Baanders and Marcel Canoy, “Ten Years of Taxi Deregulation in the Netherlands – The case for Re-regulation and Decentralisation”, Association for European Transport and contributors, 2010, available at http://abstracts.aetransport.org/paper/index/id/3411/confid/16

3The notion of online-enabled platform has, for instance, has been used by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). See infra footnote 45. While Uber is the best known online-enabled platform, other companies such as Lyft or Sidecar provide comparable services.

4See, e.g., Sara Silverstein, “These Animated Charts Tell You Everything About Uber Prices In 21 Cities”, Business Insider, 16 October 2014 at www.businessinsider.com/uber-vs-taxi-pricing-by-city-2014-10

5Sarah Mishkin, “Uber raises $1.6bn from Goldman clients”, Financial Times, 21 January 2015 (indicating that Uber had a $40bn valuation”)

6See Matthew Field, “’Uber protest’ by black cab drivers brings traffic chaos to Westminster”, The Guardian, 26 May 2015.

7James Fontanella-Khan, “€10,000 fines threat for Uber taxis in Brussels”, Financial Times, 15 April 2015.

8Eric Auchard and Christoph Steitz, “German court bans Uber’s unlicensed taxi services”, Reuters, 18 March 2015, available at www.reuters.com/article/2015/03/18/us-uber-germany-ban-idUSKBN0ME1L820150318

9“Italian court bans unlicensed taxi services like Uber”, Reuters, 26 May 2015, available at www.reuters.com/article/2015/05/26/us-italy-uber-idUSKBN0OB1FQ20150526

10Harriett Alexander, “Judge in Spain bans Uber taxis”, The Telegraph, 9 December 2014.

11Frances Robinson, “Brussels to Propose New Laws Governing Uber”, 24 November 2014, available at blogs.wsj.com/digits/2014/11/24/brussels-to-propose-new-laws-governing-uber/

12For an historical perspective, see Paul Stephen Dempsey, “Taxi Industry Regulation, Deregulation & Reregulation: The Paradox of Market Failure”, (1996) 24 Transportation Law Journal 73.

13See, e.g., House of Commons – Transport Committee, The Regulation of Taxis and Private Hire Vehicle Services in the UK, Third Report of Session 2003–04 Volume I, at p. 15, available at www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200304/cmselect/cmtran/251/251.pdf

14See Dempsey, supra note 11, at p. 77.

15See “The Taxi Market in Ireland: To Regulate or Deregulate?”, Public Policy.IE, 23 October 2014, available at http://www.publicpolicy.ie/the-taxi-market-in-ireland-to-regulate-or-deregulate/

16Dempsey, supra note 11, at 75.

17See “The Taxi Market in Ireland”, supra note 14.

18See supra note 14.

19See Dempsey, supra note 11, at 102 et seq.; Baanders and Canoy, supra note 1; Roger F. Teal and Mary Berglund, “The Impacts of Taxicab Deregulation in the USA”, Journal of Transportation Economics and Policy, January 1987, 37.

20Id.

21See Bill Gurley, “A Deeper Look at Uber’s Dynamic Pricing Model”, Above the Crowd, available at http://abovethecrowd.com/2014/03/11/a-deeper-look-at-ubers-dynamic-pricing-model/

22Id.

23See “Pricing the Surge”, The Economist, 29 March 2014.

24See Gurley, supra note 20.

25Id.

26See supra note 3.

27See Sergiy Golovin, “The Economics of Uber”, Bruegel, 30 September 2014, available at http://www.bruegel.org/nc/blog/detail/article/1445-the-economics-of-uber/

28See supra notes 6 to 9.

29See Julia Fioretti, “Uber files complaints against German and Spanish bans”, Reuters, 1 April 2015, available at www.reuters.com/article/2015/04/01/uber-eu-complaint-idUSL6N0WY2TP20150401

30The duty of “sincere cooperation” set out in Article 4(3) TEU requires Member States to take appropriate measures to “ensure fulfillment of the obligations arising out of the Treaties or resulting from the acts of the institutions of the Union” as well as to “refrain from any measure which could jeopardise the attainment of the Union’s objectives”.

31In theory nothing prevents to combine Article 102 TFEU with Article 4(3) TEU, but this provision has been essentially applied in the context of Article 101 TFEU. As will be seen below, State measures raising issues in relation to abuses of a dominant position have usually arisen in the context of Article 106(1) TFEU.

32See Case 13/77, Inno v. ATAB, [1977] ECR. 2115.

33See, e.g., Case 231/83, Cullet v. Leclerc, [1985] ECR. 305 (challenge to a fixed minimum price failed because the minimum price was a pure State measure unrelated to any agreement between competitors).

34See, e.g., Case 136/86, BNIC v. Yves Aubert, [1987] ECR. 4789; Case 66/86, Ahmed Saeed, [1989] E.C.R. 803.

35Article 1(4) of Directive 2008/63

36See, e.g., Article 1.4 of Directive 2008/63 on competition in the markets in telecommunications terminal equipment, O.J. 2008, L 162/20.

37Case C-376/08, Serrantoni Srl, [2009] ECR. I-12169, at § 41.

38Joined cases C-34/95, 35/95 and 36/95, De Agostini, [1997] ECR I-3843, at § 52.

39“Given the essentially local significance of taxi services and in line with the principle of subsidiarity, existing Community legislation in the field of transport does not cover taxi services”, Answer given by Commissioner Tajani on behalf of the Commission to a Parliamentary Question, 22 June 2009, E-3230/2009

40See supra note 4.

41Some taxi companies are, for instance, relying on Hailo, technology platform that matches taxi drivers and passengers through its mobile phone application. See https://www.hailoapp.com/

42See Danny King, “Report finds agents losing ground to online”, mobile bookings, 23 December 2014, available at www.travelweekly.com/Travel-News/Travel-Agent-Issues/Report-finds-agents-losing-ground-to-online-and-mobile-bookings/

43Although companies, such as Airbnb are also facing regulatory changes, see Roberta A. Kaplan and Michael L. Nadler, “Airbnb: A Case Study in Occupancy Regulation and Taxation”, 82 (2015) U Chi L Rev Dialogue 103, https://lawreview.uchicago.edu/page/airbnb-case-study-occupancy-regulation-and-taxation

44This is, for instance, what has been done in California where the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) created a specific regime to apply to “companies that provide prearranged transportation services for compensation using an online-enabled application (app) or platform to connect passengers with drivers using their personal vehicles”. See CPUC Establishes Rules for Transportation Network Companies, Press Release, 19 September 2013, available at http://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Published/G000/M077/K132/77132276.PDF This regime establishes 28 rules and regulations for Transportation Network Companies whereby they must obtain a license from the CPUC to operate in California; require each driver to undergo a criminal background check; establish a driver training program; implement a zero-tolerance policy on drugs and alcohol; hold a commercial liability insurance policy that is more stringent than the CPUC’s current requirement for limousines, requiring a minimum of $1 million per-incident coverage for incidents involving TNC vehicles and drivers in transit to or during a TNC trip, regardless of whether personal insurance allows for coverage; and conduct a 19-point car inspection. Id.

45That is, for instance, the case in the electronic communications field where only companies with significant market power (typically the incumbent telecommunications operator) are subject to regulatory remedies. See European Commission, Regulatory framework for electronic communications in the European Union, available at https://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/sites/digital-agenda/files/Copy%20of%20Regulatory%20Framework%20for%20Electonic%20Communications%202013%20NO%20CROPS.pdf

46See, e.g., Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, 1995 OJ L281/31.

47See Josh Barro, New York City Taxi Medallion Prices Keep Falling, Now Down About 25 Percent, The Upshot, New York Times, 7 January 2015.

48For an excellent discussion of the question of compensation, see Michael J. Trebilcock, Dealing with Losers – The Political Economy of Policy Transitions, Oxford University Press, 2014.

49See Edmund W. Kitch, “Can we Buy our Way out of Harmful Regulation” in Donald L. Martin and Warren F. Schwartz, Deregulating American Industry: Legal and Economic Problems, Lexington Books, 1976, 51, 54.

50Id. at 52.

Featured News

Massachusetts AG Sues Insulin Makers and PBMs Over Alleged Price-Fixing Scheme

Jan 14, 2025 by

CPI

Apple and Amazon Avoid Mass Lawsuit in UK Over Alleged Collusion

Jan 14, 2025 by

CPI

Top Agent Network Drops Antitrust Suit Against National Association of Realtors

Jan 14, 2025 by

CPI

Weil, Gotshal & Manges Strengthens Antitrust Practice with New Partner

Jan 14, 2025 by

CPI

Russian Court Imposes Hefty Fine on Google for Non-Compliance with Content Removal Orders

Jan 14, 2025 by

CPI

Antitrust Mix by CPI

Antitrust Chronicle® – CRESSE Insights

Dec 19, 2024 by

CPI

Effective Interoperability in Mobile Ecosystems: EU Competition Law Versus Regulation

Dec 19, 2024 by

Giuseppe Colangelo

The Use of Empirical Evidence in Antitrust: Trends, Challenges, and a Path Forward

Dec 19, 2024 by

Eliana Garces

Some Empirical Evidence on the Role of Presumptions and Evidentiary Standards on Antitrust (Under)Enforcement: Is the EC’s New Communication on Art.102 in the Right Direction?

Dec 19, 2024 by

Yannis Katsoulacos

The EC’s Draft Guidelines on the Application of Article 102 TFEU: An Economic Perspective

Dec 19, 2024 by

Benoit Durand