The Italian Competition Authority’s Decision in the Amazon Logistics Case: Self-preferencing and Beyond

By Claudio Lombardi1

Introduction

In a long-awaited decision, the Italian Competition Authority (ICA) has found Amazon in breach of Article 102 TFEU. The ICA has defined the anticompetitive conduct in question as ‘self-preferencing’,2 although this term may not fully or adequately explain Amazon’s actions.

The case concerns a series of exclusive and irreplicable benefits accorded to vendors subscribing to ‘Fulfillment by Amazon’ (FBA), with which Amazon aimed at gaining a dominant position in the Italian market for logistics services at the expense of other efficient competitors, consumers, and competition as a whole.To determine whether this conduct infringed Art. 102 TFEU, the ICA has followed the standard method of defining the relevant market before establishing dominance and its abuse. This article unpacks the ICA’s decision and considers its contribution to the development of competition law in this sector. In particular, the article considers some of the differences between this decision and the Google case regarding the definition of self-preferencing practices, claiming that this definition might be inadequate to fully describe Amazon’s conduct and the ICA’s decision. Finally, the article discusses some of the drawbacks and limitations of the ICA’s decision.

II. The facts of the case: a primer

Amazon’s website operates two sales channels simultaneously. On the one hand, it sells goods that it owns directly. On the other hand, it operates as a platform where third-party vendors can sell their goods (i.e. the Amazon Marketplace, ‘AM’), similar to other e-commerce platforms such as eBay.

The conduct at issue concerns the relationship between Amazon.it, third-party sellers, and the logistics service providers operating on the AM. Currently, a third-party seller active on Amazon can manage the logistics of its products in two ways. It can independently operate the storage, logistics, and delivery; or outsource it to an independent operator. This operator can be Amazon itself, or another firm. If the seller decides to use Amazon’s logistics network (ALN), they are requested to purchase a service called ‘Fulfilled by Amazon’ (FBA). If they entrust an independent logistics firm instead, Amazon defines the operation as a ‘Merchant Fulfilment Network’ (MFN).

FBA is an integrated logistics service that includes: (i) warehousing and inventory management for retailers at Amazon’s distribution centres; (ii) fulfilment of orders received on Amazon.it, including packaging and labelling; (iii) shipping, transportation, and delivery; (iv) returns management; and (v) customer service.

Amazon’s warehousing and shipping rates have increased considerably in recent years. Despite this, most third-party sellers use the FBA services as, on the whole, it is preferable to switching to an independent logistics service provider because of the unique advantages FBA gives on the Amazon Marketplace.

The hypothesis that the ICA sought to verify in this case was whether these benefits were designed, or were anyway sufficient to allow Amazon to leverage its dominant power in the e-commerce sector to monopolize the market for e-commerce logistics to the detriment of competition in the industry.

Figure 1: Amazon Fulfilment Centre

Source: eSellerhub

III. The relevant markets

According to the ICA, the conduct mainly concerned two markets:

- the market for intermediation services on e-commerce platforms; and

- the market for logistics services for e-commerce.

i. The market for intermediation services on e-commerce platforms.

Brokerage services on e-commerce platforms (marketplaces) are provided by the owner and operator of the platform to third-party vendors selling their products on the platform. Considering Amazon to be a two-sided transaction platform, the ICA defined the relevant market on each side of the platform using a multi-market approach.3

According to the ICA, the market for the supply of intermediation services on e-marketplaces is characterised by the absence of demand-side substitutability with other retail channels. Brick and mortar sales, sales through proprietary websites, and price comparison services are complementary to e-commerce sales rather than substitutes. As the authority argues, for both consumers and sellers, these are “substantially different sales channels, complementary and not alternative to each other” (Page 142). Thus, e-commerce transaction platforms were considered to be an independent relevant market. The ICA included all e-commerce marketplaces in this category, both hybrid (such as Amazon itself, selling proprietary products and third-party products simultaneously) and traditional e-commerce platforms selling only third-party products (such as Ebay).

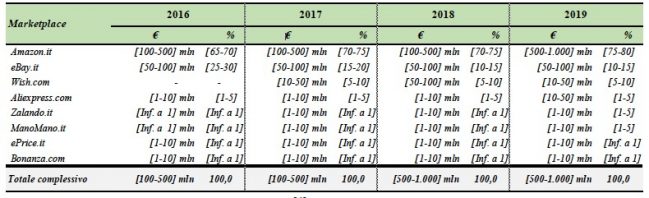

Based on this market definition, the ICA concluded that Amazon occupied a position of super-dominance in the Italian e-commerce market. All market indicators showed that Amazon had increased its market shares in the e-commerce sector steadily (to about 80% in 2019), together with its popularity amongst third-party sellers, and that its main competitors were marginalized.

Figure 2: Revenues of e-commerce operators.

Source: ICA

Moreover, the market is also characterized by high barriers to entry, due to “loyalty and stickiness of consumer preferences, variety and breadth of services offered, network effects, brand popularity and reputation all hinder the possibility of reaching a minimum size sufficient to exert a competitive constraint” (p. 167).

ii. The market for logistics services for e-commerce.

Logistics services, in this case, encompass order fulfilment, warehouse management, and delivery (in some cases, including also returns). The ICA considered the rapid expansion of a national market for e-commerce logistics services, in which players with different characteristics and sizes operate on the supply side. Given the high start-up costs, several logistics companies are changing their business strategy through vertical integration or collaboration agreements with other companies. The B2C logistics for e-commerce requires specific investments given its characteristics, such as instant fulfilment of multiple small orders on demand, which sets it apart B2B logistics, where some of these companies were already operating.

The growth of the e-commerce industry has also attracted new entrants in the markets for integrated logistics services in Italy.4 However, as the type of service needs dedicated technologies, space, know-how, and workers, these new entrants have made significant investments, especially for the adoption of advanced technologies to integrate the different logistics phases.

These operators offer a fulfilment service dedicated to e-commerce, similar to FBA.

However, their investment is conditioned upon the possibility of tapping into a sufficiently large pool of demand.

IV. The Abuse

The ICA has concluded that Amazon was able to illegally leverage its position of super dominance in the Italian e-commerce market to gain a significant advantage over competing operators in the Italian e-commerce logistics industry to the detriment of third-party sellers and consumers.

The strategy, according to the antitrust authority, was also likely to strengthen Amazon’s dominant position in the national market for intermediation services on marketplaces.

The advantages of FBA are, in particular: (i) non-application of performance metrics to third-party sellers; (ii) obtaining the Prime badge; (iii) higher probability of being awarded the BuyBox; (iv) possibility to participate in special events and offers; and (v) eligibility for “Free Shipping via Amazon”.

In particular, access to Prime members seems to be crucial for most vendors as the purchases made by Prime consumers in 2019 amounted to approximately [80-90%] of the total value of transactions on Amazon.it, and [70-80%] of the products purchased by these users had a Prime badge. (Page 187)

The ICA also observed that the conduct had the effect of discouraging retailers from multi-homing their logistic services. The high costs of the FBA service, including the MCF multi-channel management, and the costs associated with operating multiple warehouses simultaneously were already sufficient to disincentivize retailers from multi-homing. In addition to that, the ICA noted that Amazon’s “abusive pressure” to adopt their logistics services was also geared towards pre-empting multi-homing and that the strategy had already worked in their favor as “reflected in the drastic worsening of the competitive position of the second player in the brokerage services market, eBay” (Page 188).

Amazon argued that the benefits were bestowed only on FBA subscribers because of the “superiority” of Amazon’s services, which would ensure a certain level of quality. The ICA, however, considered that Amazon failed to provide any evidence of said greater quality of service. Moreover, the attribution of sales advantages was not linked to the sales performance of retailers. On the contrary, FBA retailers received a more lenient treatment in their evaluation and control requirements than did those who turned to MFN.

A. Classification of the Abusive Practice

The ICA defines the conduct above as “a single, complex and articulated exclusionary strategy, implemented by the Amazon group in violation of Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)” (188).

More specifically, the ICA defined the conduct as self-preferencing, observing that Amazon used its super-dominant position in the e-commerce industry to increase third-party seller demand for its logistics service, to the detriment of competing services.

Amazon has argued that their conduct cannot be classified as an abuse ofdominant position in the form of self-preferencing due to the lack of relevant case law. The company has also highlighted the differences between this case and the Commission’s recent decision in Google Search (Shopping), the only case so far in which self-preferencing was qualified as autonomous abusive conduct. Moreover, Amazon did not coerce retailers to adopt FBA because they remained free to decide whether they wanted to use the service, and no minimum inventory requirements were imposed.

The ICA respondedby observing that the designation of the conduct as abusive does not depend on whether it falls within a particular classification, but on the identification of substantive features of the abusive conduct. (P. 190)

Regardless of the nomen iuris used for the specific conduct, the ICA held that it has submitted all evidence needed to prove an abuse of dominance.

Indeed, the classification of the conduct as self-preferencing might be inaccurate if one considers a narrow interpretation of the Google Shopping case. However, the conduct is not about tying either, let alone bundling of services. The conduct hinges more precisely on leveraging the company’s dominance in the e-commerce sector (through special offers and treatment) in order to favor the purchase of its logistics services, which were neither better priced nor necessarily of better quality than competing logistics services.

In other words, “Amazon has artificially combined two distinct services: the presence on the platform at remunerative conditions (possibility of not being subject to the evaluation of one’s own performance, of offering products with the Prime label, of selling during special events and of having a high chance of winning the BuyBox) and the FBA service for the fulfilment of orders – in order to create an illicit incentive to purchase FBA, in the absence of alternative ways of accessing the same advantages, apart from the use of FBA” (Page 191).

B. Efficiencies

According to the ICA, there is no commercial or technical reason to justify the link between the benefits granted to subscribers and FBA usage, nor does the conduct find justification on grounds of efficiency. In other words, while the evidence suggests that other logistics operators are able to provide services of comparable quality,5 the respondent undertaking has failed to prove the contrary. And, indeed, the ICA observed, Amazon has introduced a Seller Fulfilled Prime (SFP) program in 2021, in the midst of the ICA’s investigation. Thanks to SFP, sellers can undergo a qualification process that recognizes their warehouse management capabilities according to standards deemed adequate to the Prime experience. Then, using Amazon-approved delivery services deemed “suitable,” sellers may access the same benefits guaranteed to third-party sellers using FBA. However, SFP did not put an end to the anticompetitive conduct as it is not an alternative to FBA.

The SFP service is reserved for a particular class of retailers and conditioned to strict contractual limitations. SFP is geared toward retailers selling products with a low turnover rate or needing more flexibility in the provision of their service, such as packaging. The high tariffs charged by Amazon for long-term storage of products and the high standardization of certain elements of the service render Amazon’s marketplace either too expensive or too restrictive for these retailers. The ICA reckoned that they ultimately represent a portion of the demand for logistics services that is unreachable to Amazon, as it does not fit the FBA conditions.

To date, under SFP, Amazon does not merely set the standards necessary to qualify for and obtain the Prime label, but also defines the terms and conditions of the contractual relationship between SFP sellers and Prime carriers, going so far as to negotiate with the latter the price of their delivery services to sellers. Thus, managing the fulfilment of an order from a third-party seller included in SFP is still entirely dependent on Amazon, both in the choice of carrier and in the terms and conditions of the service provided to sellers.

Such a constraint was deemed as “completely unjustified and invasive of the freedom of negotiation between the carrier and its customers” (Page 209).

Today’s SFP does not allow, therefore, the emergence of an autonomous offer, independent from Amazon, capable of intercepting the demand for delivery services and warehouse logistics – or integrated logistics – offered by Prime level to retailers on Amazon.it.

In this sense, FBA is not only in competition with the integrated logistics services offered by other operators, but is also able to intercept the demand for carrier delivery services only, expressed by retailers who carry out in-house upstream logistics activities (Page 213)

V. The Effects of the Abusive S qtrategy

The investigation has uncovered several exclusionary effects related to the conduct.

First, the conduct had the effect of excluding potential competition, as well as industrial and technological development. By linking all the benefits in terms of visibility and increased sales performance on the marketplace to the FBA subscription, Amazon’s strategy has succeeded in curbing the development of competing integrated logistics services by innovative operators.

The second anticompetitive effect concerns operators that had already invested in this market but were not given the opportunity to “compete on equal terms with Amazon”. In order to reach the minimum efficient size and be competitive in the market, new e-commerce logistics operators need to intercept the demand of a significant number of players, which can be found only on the AM (Page 213).

Third, the conduct also has the effect of increasing Amazon’s power in the delivery industry. The use of third-party couriers for delivery has declined from 100% in 2016 to 30-40% in 2019. (Page 216) In this way, Amazon has further increased its bargaining power vis-à-vis other market players which, being both competitors and suppliers of the delivery service, see their ability to react to Amazon’s strategies increasingly diminished.

A. Effects on Other E-commerce Platforms

Amazon’s alleged conduct has also eroded the market shares of other e-commerce platforms as it made it more difficult to multi-home logistics services and thus operate on these platforms and on Amazon simultaneously. While Amazon offers a multi-channel logistics service (MCF), very few retailers adopted it due to the high operating costs. (Page 220)

Equally important because of the confusion it is likely to generate in consumers is the fact that a retailer’s order packages handled through MCF are marked with the Amazon logo even when the order comes from a competing platform. This is a marketing choice that can “cannibalize” a retailer’s sales on other platforms and, consequently, decrease the profitability of a multi-homing option. (Page 221)

As a result of this strategy, many retailers have left other marketplaces to be active only on Amazon.it, to the detriment of competition from other e-commerce platform operators. (Page 222)

VI. The Sanction

The decision includes a 1.2 billion euros fine, a cease-and-desist order, and a set of behavioral remedies. The hefty fine imposed by the antitrust authority in this decision was justified by the need to ensure effective deterrence of the sanction. Moreover, consideringthat the Amazon group achieved a global turnover in 2020 of more than €330 billion, and the importance of Amazon at the global level, the ICA increased the amount of the sanction by 50%. (Page 231)

Perhaps even more importantly for the e-commerce behemoth, the ICA has imposed additional measures meaning Amazon has to cease the anticompetitive conduct and offer equal treatment to all vendors using logistics operators that meet objective standards for the fulfilment of online orders. These standards need to be clearly defined, reasonable, transparent, and applied in a non-discriminatory manner. (Page 235)

The decision states that this can be achieved by reconfiguring the current SFP programme so that Amazon defines such standards alongside requirements for sellers to participate in SFP, but refrain from any intermediary role between third-party sellers and the logistics operators. The defined standards will be applied uniformly to offers operated by Amazon through its logistics network (i.e., Amazon Retail offers and those of third-party retailers participating in FBA) and to all offers operated by third-party sellers that qualify in SFP. (Page 235)

Moreover, SFP and FBA’s sales shall be subject to the same system of monitoring and verification of compliance with the Prime standards. Monitoring of compliance with the standards and any changes to these standards should be carried out by an independent trustee.

Amazon will have to give full visibility on its platform and in its promotional campaigns to the existence of the SFP programme and the possibility to access Prime via SFP. (Page 236)

Conclusion

The ICA’s decision comes at a time when a handful of digital platforms have accumulated sweeping powers in the real economy, while their scope has also crept to include formerly unrelated sectors. Such concerns were also lately addressed with the adoption of the EU Digital Markets Act.

In an official statement, Amazon has revealed that they will appeal the ICA’s decision because the sanction and obligations imposed are unjustified and disproportionate. The e-commerce behemoth sees its role as an essential complement of small and medium-sized businesses in the country and a driver to their growth. As Amazon’s logistics services are optional, the company argues in the official statement, retailers choose them for the higher quality offered, not because they are coerced to do so.

Moreover, the company contests, in the same statement, also its position of dominance in the Italian retail industry, claiming that the market definition should include all retail channels (online and offline).

It seems, therefore, that the appeal to the administrative court will not be limited to the sanctions, despite the initial narrow focus of the statement. Amazon may consequently try to challenge the decision on all its substantive elements, from the market definition to the imposition of remedial measures.

The ICA has defined a relevant market including most of the e-commerce platforms (traditional, proprietary, and hybrid, horizontal and vertical), but excluding brick-and-mortar sellers. Assuming that Amazon’s dominance in the Italian e-commerce market will be confirmed, the administrative court will have the role to establish whether Amazon fell short of its special responsibility not to allow its behaviour to impair genuine and undistorted competition (Intel v Commission, C‑413/14 P, U:C:2017:632, paragraph 135).

Amazon’s objections finding that there are differences with Google/Alphabet’s self-preferencing case are not misplaced, but not for the reasons for now only sketched out by the company.

Alphabet relied on its own platform alone to redirect consumers by fine-tuning the website’s design. Amazon, on the other hand, had set up a series of connected contractual arrangements with third parties to create the exclusionary effects under scrutiny. Moreover, although not sufficiently evidenced, the ICA’s investigation suggests that Amazon may be exploiting its position of dominance. The decision often mentions the fact that Amazon’s logistics services are more expensive than the competition. But again, the ICA focuses on the exclusionary effects of the infringement, thus purporting little evidence on this point.

The case law shows that not every exclusionary effect is inherently harmful to competition, because competition on the merits might result in the elimination or marginalization of less efficient competitors (see Post Danmark C‑209/10, EU:C:2012:172, paragraph 22, and Intel v Commission C‑413/14 P, EU:C:2017:632, paragraph 134). However, in this case, the set of advantages set up by Amazon are designed or at least have the effect of excluding, from what seems to be an essential facility, as efficient competitors. When asked, Amazon was not able indeed to submit evidence of the superiority of its logistics services. While, on the contrary, most merchants vouched for some of the competitor’s quality of service but declared their intention to stick to Amazon’s for the higher visibility this would bring.

Amazon’s conduct does not resolve in an outright refusal to grant access to an essential facility, but rather in imposing unfavourable conditions leading to the elimination of competition in the e-commerce logistics market. Moreover, this conduct has had the effect of reinforcing Amazon’s dominance in the e-commerce sector by hindering multi-homing. In other words, Amazon’s conduct deviates from competition on the merits when it leverages its super dominance in the e-commerce to exclude competitors in the logistics market.

The lack of definitive evidence of the superiority of Amazon’s logistics also hampers the possibility of assessing the pro-consumer benefits of such practices. On the other hand, in the ICA’s decision there is little evidence about direct consumer harm. Although, on this point, it is important to remark that Article 102 TFEU protects consumers not just from acts that directly hurt them, but also from practices that harm them indirectly through their impact on competition (see Post Danmark, C‑209/10, EU:C:2012:172, paragraph 20).

Finally, the measures adopted, albeit severe, could not solve the problem of removing the barriers to multi-homing. As most sellers have already adopted FBA, and considering the high switching and the multi-homing costs, logistics operators may still find it difficult to enter this market.

Even assuming that the Italian administrative courts will confirm the ICA’s decision on the merits, it is likely that its effects will be mostly palliative, especially for other e-commerce players.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 Lecturer, University of Aberdeen, School of Law, and director of the Eurasian Centre for Law, Innovation, and Development (ECLID).

2 Italian Antitrust Authority decision A528, 30 November 2021.

3 Which is the approach followed by the European Commission and the European Court of Justice in several cases concerning multisided platforms, including AT.29373, Visa International – Multilateral Interchange Fees, 2002, 43; and also joined cases 2007: AT.34579, MasterCard; AT.36518, EuroCommerce; AT.38580, CommercialCards, 283-329; and T-111/08, MasterCard, EU:T:2012:260, 21.

4 Such as the DotLog consortium, Olimpia, FacileWeb, ConnectHub, Ceva, Save.

5 Warehouse logistics companies stated that they are able to process an order in a very short time frame from the moment of the customer’s request (even in less than one hour) and that they therefore have the organisational capacity and efficiency necessary to meet Amazon’s timeframe for the fulfilment of an SFP order.

Several retailers heard at the hearing also confirmed the ability of warehouse operators other than Amazon to meet order fulfillment times and, more generally, a level of service adequate to their requirements.

As to the ability of carriers operating in Italy to deliver orders according to the criteria required by Amazon for SFP, all operators stated that these service levels are similar to those normally offered to their customers and, in some cases, guaranteed to Amazon itself for AFN parcel deliveries (Page 210)

Featured News

US Judge Allows COVID-Era Price Gouging Lawsuit Against Amazon to Proceed

Jan 6, 2026 by

CPI

DOJ Signals Continued Scrutiny of Real Estate Commission Rules

Jan 6, 2026 by

CPI

Morrison Foerster Announces 17 New Partners for 2026

Jan 6, 2026 by

CPI

UK Presses X to Curb AI-Generated Deepfake Images as Europe Raises Alarm

Jan 6, 2026 by

CPI

NASCAR Commissioner Steve Phelps to Step Down Following Antitrust Lawsuit Fallout

Jan 6, 2026 by

CPI

Antitrust Mix by CPI

Antitrust Chronicle® – CRESSE Insights

Dec 16, 2025 by

CPI

Learning from Divergence: The Role of Cross-Country Comparisons in the Evaluation of the DMA

Dec 16, 2025 by

Federico Bruni

New Regulatory Tools for the EU Foreign Direct Investment Screening and Foreign Subsidies Regulation

Dec 16, 2025 by

Ioannis Kokkoris

“Suite Dreams”: Market Definition and Complementarity in the Digital Age

Dec 16, 2025 by

Romain Bizet & Matteo Foschi

The Interaction Between Competition Policy and Consumer Protection: Institutional Design, Behavioral Insights, and Emerging Challenges in Digital Markets

Dec 16, 2025 by

Alessandra Tonazzi